Calf management in winter – part 1

22. Dezember 2021 — Calf Feeding, Calf Husbandry, Calf management — #Power supply #Calving assistance #Calf Health #Winter #Winter managementWhat do calves really need in winter?

Calves grow best in an outdoor climate. This is the experience of many farmers, because an outdoor climate means lots of fresh air and consequently few respiratory diseases. However, an outdoor climate also means that calves are exposed to normal temperatures throughout the year. It can get very hot in summer and very cold in winter for the calves.

This article is about

- The question of why calves have a higher heat requirement than cows

- The necessary energy that the calves require in winter

- The influence of cold temperatures on calf health

Young calves have a higher heat requirement than adult cows. There are several reasons for this:

- They have very little in the way of fat reserves – particularly directly after birth – which provide both energy supply and heat insulation for their bodies.

- Their small body size results in an unfavourable ratio to body surface area. The surface area of calves is proportionately greater than that of cows, meaning that more heat energy is lost.

- The rumen is not yet well developed in the first few weeks of life. This means that calves do not yet benefit from the heat production of the bacteria in the rumen, as is the case with cows, for example.

- Young calves lie down a lot and do not yet engage in much activity. As a result, they do not generate much heat in their muscles. This effect is intensified if the calves are kept in small pens where they cannot move around sufficiently.

The optimum ambient temperature for calves is between 10 and 25 °C. In the literature, there are repeated references to the fact that the so-called "thermoneutral zone" of calves aged up to 3 weeks begins at about 15 °C. This means that a calf does not require any additional energy above this temperature to maintain its own body temperature. Normal metabolic activity and exercise are quite sufficient for this.

Below this temperature threshold, a calf expends extra energy in order to maintain its body temperature. This energy is then no longer available for growth.

However, it is particularly critical that the calf's immune system and stress resistance are the first to be affected. It is only when temperatures drop further that it also becomes apparent that body growth is restricted. This means that calves become more susceptible to diseases even at "slightly" cold temperatures (for example 5–15 °C).

Calves' energy requirements in winter

A calf with a body weight of 50 kg and a daily growth of 400 g needs approx. 1 kg of CMR per day. However, if growth of 1,000 g is expected, about 1.5 kg of CMR needs to be provided. These values apply within the thermoneutral zone, for example at 20 °C (according to the LfL Gruber table).

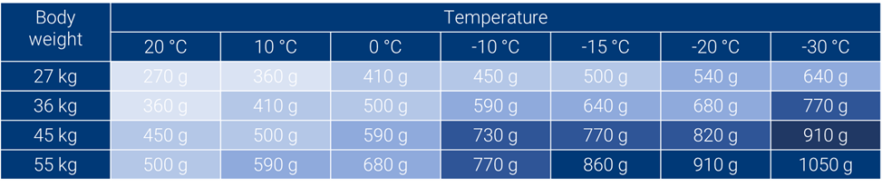

To add to this, an see from Michael Steele's Table 1 that young calves weighing 45-55 kg need about 450-500 g of milk solids (for example CMR) per day on a warm summer day just to meet their maintenance needs. As more milk is fed, it is available for growth. However, if the outside temperature drops below freezing, 50 % more energy has to be used to maintain body temperature. If you also take into account the growth of the animals, the total energy requirement increases by approx. 20-30 % at approx. 0 °C.

Influence of cold temperatures on calf health

- The CMR was prepared with 118 g/l of water as recommended by the manufacturer. As a result, the CMR group was supplied with approx. 25 % less energy than the whole-milk calves. Furthermore, both groups were fed relatively little milk: 4 l per day when temperatures were above -4 °C and approx. 5-6 l when it grew colder.

- The differences in disease susceptibility occurred particularly in the winter months. The CMR group was then ill significantly more often and had a significantly higher mortality rate in the cold season.

Morbidity and mortality of calves in different seasons according to Sandra Godden, 2005

| Fed with CMR (215 calves) | Fed with whole milk (223 calves) | |

|---|---|---|

| MORBIDITY (disease) | ||

| All year round | 32.1 % | 12.1 % |

| Winter | 52.4 % | 20.4 % |

| Summer | 12.7 % | 4.4 % |

| MORTALITY (loss) | ||

| All year round | 11.6 % | 2.2 % |

| Winter | 21.0 % | 2.8 % |

| Summer | 2.7 % | 1.7 % |

In this light, table 2 could be read as follows: While in the summer months the full-milk calves were relatively healthy (morb. 4.4 %) despite a limited supply, the CMR calves, with 25 % less energy, were also more susceptible to diseases over the summer (morb. 12.7 %). However, this had no effect on mortality during the summer (1.7 v. 2.7 %). In winter, the increased milk quantity was not able to cover the higher energy requirements in both groups and the calves were more susceptible to disease. CMR calves had a particularly hard time, with half (52.4 %) falling ill and an eighth (12.7 %) dying. The rate of disease and loss in the whole milk calves was higher than in the summer months, but still within acceptable limits.

This blog article was written taking inspiration from the "Cold Weather Calf Management & Feeding" webinar in December 2021. In some cases I found useful advice and information in the two blogs by CalfTel und CalfStar, which I elaborated here. It is certainly worth taking a look at them. Many thanks to the authors Kelly Driver and Minnie Ward.

Read also the second part of this blog with 12 unbeatable tips for managing your calves better in winter.